1988 Dec 2 – JESUS.THE.NON VIOLENT RESISTER

Rev. Frank Cordaro

The eyes you bring to the scriptures are as important as the text you read. As a pastor, I struggle with a new set of scriptural texts each week I have consistently seen in my studies a resistance premise built into the Gospels. live discovered in Jesus the clearest example. of a nonviolent resister. I have found in the early Christian Churches a collection of resistance communities trying to follow the non violent Jesus. Seeing this resistance premise in the scriptures has a lot to do with the experiences I bring to my ministry.

Before ordination I lived and worked at the Des Moines Catholic Worker for seven years. I got to see the wo r 1 d through the eye s of the poor . For those who live in the sub human environment of poverty the system is failing them and their numbers are growing. It was easy to see from our soup lines and hospitality houses that our nations troubles are many, systematic in nature. and demonic in char-acter. We are in the !Didst of a spiritual crisis of cosmic proportions. At the heart of this spirifua1 malaise is our blind a11egience to the “BOMB”. Its phy-sical tJ1reat is awesome and ultimate. Its mere existance darkens our souls. Our continued acceptance of its logic cripples the spirit. Thereisno doubt about it ,we live in bad times. At the Catholic Worker I also: came in contact with a modest but growing resist-ance Church. These people ar~ conspiring to live lives of Biblical clear sight-edness and faithful intregity. It is a. resistance church whosesedge on the truth are the poor they have come to live with and the pri sonce 11 s they ha vecome to call home. From this resistance way my reading of scriptures takes its lead. consequently my preaching has gotten mixed reviews.

. .

I remember preaching on the Feast of St. Peter and St. Paul. The first reading was from ACTS 12/1-11. It tells of a miraculous prison escaps by St. Peter. I began my homily with a personal jail story of my own. I the.n proclaimedSt Peter and St. Paul to be famous law breakers. A parishoner later complained that he . and others did not appreciate hearing about my prison experiences from the pul-pit nor did theyappreci ate my equating St. Peter and St. Paul as famous 1 aw break. ers. In hi seyes St .Peter and St. Pau.1suffered martyrdom for their faith not for breaking any laws.

I was taken aback by hi s strongreacti on. Of course, St Peter and St. Paul died for their faith. ihey also died because they were judged and tried as law breakers and a. threat to the Roman Empire. To deny thisi sto deny the basic integrity of the narrative. How can people miss such an obvi.ou.s fact in the text? It is a bl-indness closely connected to a national obsession for law and order. Itis an ob-sessi on that borders on Idol atry.

How we as Christians have become such a 1 awand order people i sbeyond me. More importantly,it’s beyond the Gospel message we all claim. .The entire New Testament was wri tten to an underground Church. The fi rst century Church was a church of outlaws. tradition has it that all of the New Testament writers except for John were excecuted by the Roman Empire for treason; lawbreakers and outlaws ~v~ry one of them.

Even the primo act of Christianity was an act of civil disobedience. When the Roman Empire sentences someone to death, that person is suppose to remain dead. To r’lse from the dead isto break the law. The Resurection was an act of civil disobedience and the law has been after the Risen Lord ever since. We have only to r~view our rich church history of law breakers and troublemakers to know Chrt:gt’s disobedient spirit lives. A r.i stance readi ng of the Gospels fi rst starts wi th the thi ngs Jesus DID and nott9J:what he SAID. It is the narrative, the story 1 ine that is most important . Jesiwords take their meaning from the dramatic flow of his life. The four Gos-pel~~,give us the clearest picture of Jesus dramatic life story. ‘ We a’ll live our lives through our stories. Our imaginations are shaped by our sto,ries.We have,. our OWn personal stories and our family stories. Logan, the, town where r 1 i ve ,has its own hi story made up of many different stories and ev-ents that took place in the lives of the people who have lived there~ Our count- , ry has its stories by which we live. We have our faith stories by which we beleive. Most’stories have a beginning, an ending and in between a conflict to be reso1ved.

The Gospels are no different. In his talk at the Faith and Resistance Retreat hel i nCounci 1 Bluffs, Iowa> in August of 1986, Rev .Bob Beck, a Lora s College scri p- ” ture scholar, asked three questions about the conflict in the Gospel stories: What i’s the context of the conf1 i ct? How is the conf1 i ct resolved ?Whati s the arena in which the conflict is played out? Much of what follows was outlined in Father Becks’ ta 1 k.

WHAT IS THE CONTEXT OF’THE CONFLICT?

The Gospel is a .countercul tural story wi th an ,eschato 1 ogi ca 1 thrust. Eschatology is the study of the End Times. It is from this eschantological framework that the context of the Gospel conflict must be understood. From the very beginning, the faithful be1eived that the end of the world was near. If you be1eivedyour end was near’, you would most likely rearrange ‘your priorities. TheearlyChurch did by rad-ically rearranging the priorities of it’s followers in anticipation of the end of the wor1 d. ‘

By the time the Gospels were written, the Church had to deal with what appeared to ~i~ a postponement of the Parousi a. Interesting enough, di spite what seemed to be an indefinate delay all four Gospel writers took seriously the eschatological th~ rust and kept its urgency within the framework of their stories about Jesus.

T~,~.,:,New Testament is, full of eschatological thinking. Matthew’s Gospel beginsJe sY~1ifPub1ic1ife with John the Baptist stating the claim plainly IIReform your lives!1I Th:j;Beign of God is at hand!IIMt. 3/2 . The repeated claim is made throughout the Ne,w:Testament. A new age has replaced the old. The world now lives in the light .~, ., ,w~~re before it only knew the darkness. From now on love will rule over fear, peace wit) replace war, justice will come unto its own, even life now triumphs over, death. Good news for all concerned! ‘ Tfi~~n~w era has begun yet the old era is hanging on. Here is the ‘rub, the context of. the conflict. The early church was caught in a life and death struggle between the. forces of good andevi 1 in this in between time. The two eras seem to co-exist side by side in consta~t tension and friction. It’san all out battle for th’e’soul of humanity and the destiny of Creation. We have only to pick a side.

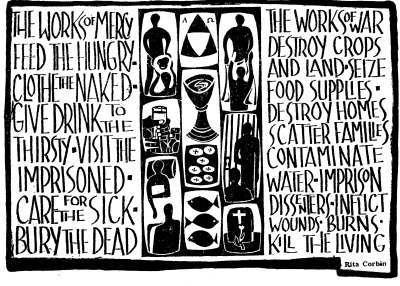

In”this struggle the followers of Jesus are not without a blue print, a plan their marching orders, something to measure their lives by. They have the Ser-mon on the Mount, the command to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, shelter the homeless, free the captives, get rid of their possessions and love all peo-ple unconditionally— especially our enemies. It is a counterculture agenda with a radical means, all that must be done, must be done without force or violence. Love is the basis and non-violent love is the means. A follower of Jesus can not seek the backing of the Law, for the laws are backed by force and violence. More often than not their efforts are made despite the Law.

A follower of Jesus is cha llenged to be a ci ti zen of the Rei gn of God, whose victory is assured at a later date, yet has claims in the here and now. Check out the fictional character of Merlin the Wizard. He lives backwards in time from the future into thepresertt. It is a follower of Jesus direction too. As they live their lives in the here and now they are claim~d by the dictates of a future Reign, challenged to bring the hope of this future time into the pre-sent.

HOW IS THIS CONFLICT RESOLVED? .

Now that we have named the conflict as a struggle between ultimate good and evil how does Jesus resolve this conflict in the Gospels? What does the dr’amatic ac-tion of the narrative tell us? Most stories that we are familiar with use what is called “Poetic JusticeU to resolve their conflicts~

Poetic Justice is when the bad guys are done in with some of their own medicine. We know the senari 0 well. The typi ca1 storybegi ns with the bad guys doing some thi ng bad to the good guys. The good guys a re innocent. As the story progresses. the goodguyseventua11y use the bad guys means to get even. The bad guy gets some of hi s own medi ci ne and the innocent 1 i ve happi lyeverafter.

The worse the bad guys the more innocent the good guys . Taken to its ultimate extension the bad guyjgoodguy conflict is a conflict between good and evil. In this respect it is like the Gospel story yet vastly different in its means of resolving its conflict. In u1 timate terms in order to use the bad guys means, the good guys must trans-form the bad guys into sub human characters. The bad guys personi fy :the evi 1 they have embraced. The more through1y the bad guy is destroyed the better the ending. The good guys who are innocent have the right,even the duty, to destroy the bad guys even if that means using the evil ones means.

A good example of this dynamic in recent times can be found in the movie “Star Wars”. The conflict is between ultimate good and evil, between the “force and the Death Planet. Early in the show Darth Vader destroys Princess lea’ splanet. I remember sitting in the theater when the Princess’ planet was destroyed. There was a gasp by the crowd at this ultimate evil act. The dictates of poetic justice demanded a simi1iar retaliation by the followers of the Force. In the end the followers of the Force do destroy the ,Death Planet. When the Death Planet was destroyed the whole theater cheered! Good triumphed over bad and everyone lived happily ever after.

Les’s you think I make to much of this good guY/bad guy story line examine our own natlonal story post World War II. For most United States Citizens their image of themselves as a ,nation is based on the perception that in World War II we came to the’i;’rescue of the rest of the world by defeating the evil empires of Germany and Japan. Since the war we have been in a life and death struggle with the forces of co~unfsm. We are the guardian of the Free World fighting the evil empire of the sO’~,e:t.pnion.We must bewill~ng ~o. use any means a~ailable to~eep the evil for cetesln check. We have even Justlfled the threatenlng of all llfe through the use of~~~uclear weapons to maintain our way of life. What makes our Nuclear weapons diff~rent from the Soviet Nuclear Weapons? The difference is, we are right and they a r~~.”‘wron g ‘1

Ifo.urbasic truths and beliefs are defined and our imaginations are shaped by our st~ries, the good guy/bad guy story line traps us in a permanent state of host-tility. The license of Poetic Justice frees the hand of the innocent to take re-venge while absolving them of guilt. For Poetic Justice to make sense the bad guys must be wrong, the more wrong the better and the good guys must be innocent, the more innocent the better. For Jesus both assertions are lies. No one is totally wrong or evil. No one is totally right or innocent.

‘. .

In the ,Gospels Jesus comes to resolve his conflict in a wholly different way. Jesus refuses to accept the two character transformations. He doesn’t identify his enem-ieswith the evil he is fighting. He refuses to depersonalize his opposition. For Jesus no one is totally innocent either. Jesus refuses to use the methods of his enemies who are out to destroy him’through violent means. The Gospel unfolds a strug-gle that is completely non violent on Jesus side. A unique non~violent resistance borrows from both traditions. Like pacifism,Jesus adheres ‘to strick non violence no matter what. Like the self defense position Jesus aggresively confronts and ex-poses the wrongs and unjustices of his time. Jesus’ non violent resistance is ex -actly what it says it is…resistance. of evil without the use of violence.

Most people in our society don’t beleivenon violent resistance is possible. We are so conditioned by our stories that in the real world the threat of State ~an-tioned and legalized violence, is the only thing keeping the world from plunging into ~barbarit state. Pragmatic ,concerns dictate the need for laws with police and cOUirts to enforce them , arm,i es to protect and defend our borders. Thi s is how peaceismaintained. Nuclear detterance is the only option open to the pragmatic mi~~9,,:Jn.our struggle against GOQless Communism. Jesus shows us a different way.

Gene-Sharp, the well known non violent strategist identifies three moments in the d~~.mic’of non violent resistance; the confrontation, the repression and the non re.;’liati on. In the synopticGaspel s most of the Gospe 1 story is spent setting up thtJ:onfrontation. The actual confrontation comes to a head in the last week of Je~;~s life. Jesus tri umphant entry into Je’rusleum and his cleansing of the Temple wer~’the acts that sealed his fate. After the street demonstration on Palm Sunday. andfthe direct action on the temple the Sanhedrin and the Romans conspire to do away with him. The repression starts in the Garden of Gethsemni where he refuses to – ~’ut up a fi ght .Both Luke and Matthew u:$ethe Garden scene to develop the theme

Of nonviolent response. In Luke one of Jesus disciples cut off thee~r of the high priest’s servant. Jesus stopped the disciple and healed the servants ear. LK. 22/51 In Matthew, Jesus response to his disciple striking the servant is to call him off sayfng If Those who 1 i ve by the sword will die by the sword.” Mt. 26/52 Clearly Jesus response to the repression he was experiencing was one of non violent retaliation.

John’s Gospel is laid out differently. Jesus does his major assault on the Temple in the second chapter. Not only does he overturn the money tables and clears the place of animals he is also pictured brandishing a whip. If charged today he would be indicted for assault to do great bodily harm. In John’s Gospel once we look beneath Jesus statements of divine foreknowledge we find a resistance fighter. Reading the linking passages between the main stories we get a picture of a Messiah who makes his rightful claim to place and honor and then is struggling to maintain his c1aim. John’sJesus is more the resistance fighter, on the lamb from town to town b~cause thi ngs were getti ng hot.

The moment of truth for Jesus in John’s Gospel comes with his trial before Pilate:

Pi late: Are you the Ki ng of the Jews?

Jesus: Do you ask this on your own, or have others told you about me?

Pilate: Am I a Jew? Your own people and Chief Priest have handed you over to me. What have you done?

Jesus: My Kingdom is not of this world. If it were troops would have fought to prevent me from bei ng handed over to them. But my kingdomi s-not of this KIND.. .In. 18-33/36

Jesus kingdom is not of this KIND? It will not use the same methods of this world. The resistance story goes on . The Chief Priest and cOLmci 1 thought they had broken the back of the Jesus movement by killing its leader. Then there was the re-surection and the Council had its hands full with the followers of Jesus.. The book of Acts is the story Of the early Churches struggles~ Judging from their actions they fully embraced the non violent resistance of their Master. Acts, chronicles an outlawed band of belei vers who were repeatedly dragged before the courts ,thrown in and out of jail, beat up and killed~ Itis a Church on the lamb in the spirit of i tsfounder.

WHAT IS THE ARENA OF THE CONFLICT IN WHICH THE GOSPELS ARE SET?

Some folks in my parishes comptain about what they tall ‘political rhetoric’ from the pulpit. They are not.use to hearing how spiritual matters are also political matters. There is a confusion about the arena in which the Gospel stories take place. The best way to show this confusion is to ask the question, “Why did Jesus go to Jerusalem?” The usual answer is that he wentto’.’Jerusalem to die for our sins. What does this answer, imply? What does it say about our Christian imagination? Jesus going to Jeruselum to die for our sins is a “sacrificial” image, a ritual event; like Abraham and Isaac on Mount Moriah. But doesn’t God reject the idea of human sacrifices? Do we think this rejection is reversed with Jesus?

Scripture scholars overwhelmingly deny that the Gospels portray Jesus as a sacrificialoffering. The sacrificial/ri’tual angle is a secondary theme at best. If anything Jesus was out to destroy this kind of religion with his attack on the Temple. Still, many in the Church today continue to stress the sacrificial as-pects of Jesus’ mission as primary and exclusive.

Who is this God that would ask Jesus to die for our sins? What is this God like? Does not thi s ki nd of God requi re a certain quota of sufferi ng, it’s pound of fl-esh to even the scales, to make satisfaction? This kind of God tends to nurse a strange taste for death. It is a spider God, a death loving God. This is not the God of the New Testament. Where does suffering fit into this kind of sacrificial theology? It presents a pi.ctureof a God who wishes us to suffer, who finds it pleasing and appeasing. . This God would have us suffer in silence, exchanging our physical pains for spir-itua1gains not in this world but in the next.

This type of thinking only feeds our self hatred. It feeds our inclination to re-fuse to resist evil. It silences us. It tells us to go with the flow and. rewards the passive Christian. this type of thinking would see in the actions off-Jesus a passive acceptance of evi 1. Jesus is the lamb ready for slaughter, the perfect sacri fi ce and nothi ng more. The Gospels paint an entirely different picture of God and the role of suffering. A good example where the sacrificial/law and order image of God is rejected by Jesus is found i nMk. 3/1-6. Jesus finds a man with a withered hand in the synago-gue. His opponents are watching him closely. Jesus asks, lilt it lawful on the Sa-bath to do good or to do harm, to save 1ife()r to ki1l?1I Translation: Is your God for life or for death? Jesus then cures the man. Immediately Jesus opponents meet with others and begin to plot his demise. Translation: Their God is for death, fur-thermore, to be for life and the God of life as Jesus Was, may mean risking your own 1 i fe.

Here is the proper place for -suffering for the Christian. It is a consequence of being faithful. It comes with our resistance to evil. It is not. something God de-sires. It is the price, the dues to be paid for our faithful lives. It is the God of life that brings Jesus to Jeruse1um. ‘Jesus takes on the evil structures of his day and for this he pays dearly. The arena therefore in which the Gospel action takes place is not some sacrifi-cial high altar set up for a calculating God. No, the primary arena is the struggle in the here and now, the interface between the forces of life and forces of death. It;s played out in the world of governments, economic structures and social institutions; in other words in the world of politics.

WHAT ABOUT TODAY?:

Having .identified Jesus as a non violent resister in the story of the Gospels it would be good now to ask the same. questions of our own times. What is th~ -Context of our conflict with the world as we make Jesus’ story our own? How are we to resolve this conflict? What arena does the conflict take place?

What is our present day context? Modern people never really payed much atten-tion to the, idea of the world coming to an end. However, with the dropping of theAtomicbombQh Hiroshima, Japan all that has changed. Today engraved in our collective human physic is the consciouness of our own self destruction. This is a unique and qua1itive1y different human experience. At no other time have we had the mechanisms in place to destroy a 11 life. This fact changes the whole geography of the human spirit. It gives us cause to re-evaluate our assessment of Escato10gy.Howmight we look at the eschatological frame work ,upon which the Gospels rest in’ this post Hiroshima world?

In the pre Atomic modern age the idea of the End Times were remote, other wordl y and something from outside our human experience. It was something thought to come from the hand of God, a divine exit and closure to creation. Today, wel i ve with the means of an End times of our own making. An estranged End Times that comes not ‘at the hand of God but from our hands. Iti s the ultimate blasphemy, a planetary abortion that promises to end all life and destroy our future. 10 embrace the escatoiogi ca 1 hope ofr. the””Gospe1 today is to let your heaven collapse into the here and now. With-the- bomb ready to steal our future we know We. .etther make it here on earth o’r forget about the after life. To let the claims of the Reign of God rule our lives is to see ourselves in a Cosmic

life and death struggle in the here and DOw. The forces of life are banning to-gethertoovercome the continued acceptance of the bomb. We either change or die. It is not:much different from Jesus~ times. We need tore-discover the sense of urgency the first Century Christians had about the End Times and set , our priortiesaccording1y. We must see. ourselves in the same life and death struggle with the forces of good andevil,as Jesus did only with the bomb we may be the last generation to put up a fight.

How is the conflict bei-ngreso lved for the presentdaYfo 11 owers of Jesus?

In respect to this question little has changed. Jesus is st;-11 our role model ~ Weare called to be nonviolent resisters to all forms of evil. We are called toresistwithoutde~humanizing the people who are caught up in the evil spirit of the’ world. We are being called ,to resist this evil Without the Use of violence. A tall order considering the state of the world today. Where is thi sbeing done? The following comes from a reflection I gave at a prayer service before the July 6, 1986 1 inecrossing at the Strategi c Command Headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska. There were 600 people at the prayer service and rally and 247 of us crossed the 1 ine. There is a growing Resi stance Church i nthi s country. It can be found in the many houses of hospitality springing up in our urban centers serving the ever increasing number of homeless people. The front line casualties of our Nuclear Economy. It can, be found in the increased number of people refusing to pay their taxes or register for the draft, saying no to the militarization of our society. It can be found in the growing Sanctuary Movement and the Pledge ‘of Resistance.’ the United States side of the Central American Liberati on Movement . . ~ i n the “Bell y of the Beast”.

It gathers for prayer and witness at Nuclear weapons plants, military installations, seats of power in ongoing faithful campaigns of pre-sence and resistance. The conscience of this Church is being formed by brothers and sisters taking hanuners in hand and enfleshing the words of the Prophet Isaiah, “They shall beat their swords into plowshares”, spending many months and years in prison, the first feeble acts of disarmament….

It is a Church in search of the soul of a nation…It will need to confront the religion of blind patriotism and empty nationalism that serves to protect and bless the Bomb… A Nationalist Spirit that can be found in everY\lajor denomination using the same book, the same sYmbols, and the same Faith to justify it’s. Bomb Allegiance. Nothing short. of a re-allignment of what it mean~ to be faithful is at the heart of the struggle… Downwardmobil i ty ,di rect identification with the poor and actsuo,f non-violent resistance are the signs of this Resistance Church and it is growing.

And finally, what is the arena of the present day conflict? Again, there has been little change. The Gospel arena today is essentially a political aren&\as it was in Jesus time. We are called to take the fight to those human politicaL.;and eco-nomic structures who are in allegiance with the Spirit of Death. the bomb has be-come the clearest and most visible sYmbol of Death in our age. Admitedly there. are many other manifestations of this death allegiance in our world today, racism, sexism, materialism, militaryismand violence in all its forms, yet they all take their lead from the spirit of the Eomb.

What might our political agenda be for the foreseeable future? Liz McAllister, a Plowshares Activist and co-founder of Jonah House in Baltimore said it best in Minneapolis in February of 1986: lilt is argued that the danger of Nuclear destruction will always be with us because, having learned the natural laws on which nuclearweapons are based, there is no way to forget them. There is a way to ease the immediate danger, to pull back the hands of the clock~ And this is it:

….by eliminating the weapons we now possess

….by getting rid of conventional (so called) weapons as well

….by replacing the system of national state sovereignty

….by reinventing politics.

….by reinventing the world…”

It is a formidable agenda but it is ours.

Liz was reminded of James Douglas, from Ground Zero, saying, “What do we do at the end of the world?[which is now] and Jim’s answer … “BEGIN A NEW ONE!II .

—————————————————