Nov 1988 v.p. Resistance & Priesthood .. a developing Model p. 3

RESISTANCE AND PRIESTHOOD -A DEVELOPING MODEL

June 1988

By Frank Cordaro

The following article was written while Frank was serving a six-month sentence at Marion Prison Camp. In it Frank outlines his own personal story in an effort to develop a model for a resister priest.

This month marks the third year of my ordination. I’m celebrating my anniversary at Marion Federal Prison Camp in Marion. Illinois. In April I was sentenced to six months for crossing a white line at Strategic Air Command Headquarters in Omaha. Nebraska. Thus far it has been a time for review and renewal.

As long as I can remember, I was always open to the idea of becoming a priest. I seriously took up the call after graduation from college in 1973 and officially became a seminarian for the Des Moines Diocese. I spent the next three years at Aquinas Institute of Theology in Dubuque and received my Master of Divinity degree.

At Aquinas I spent my first summer in the South Bronx working in a Black and Puerto Rican parish. The following summer I worked at the Catholic Worker in Davenport, Iowa. Those two experiences convinced me I needed to find a way to work for justice while living with the poor. There didn’t seem much chance of this happening if I were ordained to the Diocesan priesthood. To add to my discernment process, I had fallen in love …a major stumbling block in becoming a Catholic priest. I dropped out of the Seminary and in 1976 helped to start the Catholic Worker in Des Moines.

Seven years later after countless pots of soup, bringing three houses of hospitality into existence, distributing thousands of leaflets, standing in hundreds of picket lines and experiencing a whole bunch of arrests, the subsequent jail time and failing at love, I found myself seriously entertaining the idea of ordination again.

I was serving time at Leavenworth Federal Prison Camp in Missouri for destroying U.S. Government property. At the gate to S.A.C. a billboard displays their international motto “Peace is Our Profession.” A group of us thought some truth more important than a good paint job. So, on the Feast of the Ho1y Innocents with paint and brush in hand we crossed out the word “Peace” and substituted the word “War.” We felt we improved the sign. The judge thought differently. It was while serving time at Leavenworth that I decided to re-enter the process of priesthood again.

I knew this resistance ‘thing’ I was doing was going to demand more and more of a serious commitment. Down the line an eight-month prison sentence would be considered a gift. If I was going to measure up to the growing demands of resistance I had to take care of the unfinished business keeping me from growing in the direction that God was calling me. I needed to respond to the priestly call again but was not sure the Church would accept me. With that in mind I officially resumed my relationship with the Diocese of Des Moines and Bishop Dingman.

I don’t believe there is another Bishop in the country that would have given me a second chance, especially with my track record at the Catholic Worker. Bishop Dingman and I had a very close relationship. We had worked together on many occasions throughout the years and had grown to love and trust each other completely. It was a relationship in which both of us felt free to speak our minds and never think twice about jeopardizing our friendship. A rare and beautiful gift, a relationship I will cherish for the rest of my life. We spent a lot of time talking to each other after my release from Leavenworth. Bishop Dingman wanted to make sure I was a serious contender. He decided to send me back to the Seminary at St. John’s University at Co11egeville, Minnesota for two years. I remember telling the Bishop I thought it would be a waste of time to send me back to school. I had the necessary degree. He told me that he wanted to see how well I could survive in the Institutional Church.

I asked Bishop Dingman, ”Why not send me to a parish for two years if you want to see how well I can survive in the Institutional Church? Why send me to a seminary?” He answered, “Why do you think they made seminaries? This will be a test.” I said, “I don’t think I will like this test.” Then he said. “That is what will make it a good test.”

So I went to St. John’s and raised what hell I could, giving the institution my best shot. I spent my creative energy organizing anti-ROTC vigils, picketing University Awards banquets, threatening to occupy the ROTC offices in the Pledge of Resistance, getting arrested twice at Honeywel1 and once at a farm protest. I wrote scathing articles in the school newspapers and organized two Holy Week trips to Washington, D.C. to work with the folks at the Community for Creative Non-Violence who work with the homeless and to protest at the Pentagon with the Jonah House Community. I was a general pain in the side of the ‘status quo’ challenging everything and everybody and getting mixed reviews through it all. I learned little in the classroom but learned much about St. John’s, the Institutional Church and the state of Catholic higher education. At all times I was up front about my resistance past and intended resistance future. At the end of two years, to the surprise of many, myself included, Bishop Dingman ordained me to the Diocesan Priesthood to serve the Diocese of Des Moines.

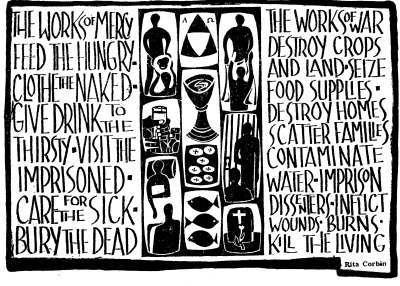

I felt well grounded in the resistance ‘thing’: my seven years at the Catholic Worker served me well. I saw resistance coming from a basic understanding of Gospel fidelity. It natura11y f1owed from my Baptismal character. Given the times, the sorry state of affairs, the Spirit cries out for Biblical activism, for a sampling of people throughout the land to embrace a resistance way of life. A life of willful positioning of’ one’s person into the cogs of the system, messing up the ‘status quo’ disregarding what goes for legitimate and getting in trouble with the law. A gathering of a people with an outlaw spirit. All done under the discipline of non-violence with an eye for the poor and the oppressed. A group of folks with an open invitation to one and all to conversion. As I see it, this resistance ‘thing’ is needed everywhere — the problem is that big. I knew its geography; it was familiar to me. What I didn’t know was how does one do resistance and be a parish priest?

Not terribly well prepared for pastoral ministry despite (because?) of my seminary training, I was assigned to the Harrison County team ministry, working with two other priests, two deacon couples, and a Religious resource person. We served the Catholic communities of Harrison County, Iowa, five different parishes in five different towns. It is a rural County on the western edge of the diocese along the Missouri River and just north of the Council Bluffs/Omaha area.

I was not assigned arbitrarily. The Team interviewed and asked for me. They were in the midst of a rural crisis. It was thought that while I grew in my priestly pastoral life, I might transplant my activism to the rural scene. I welcomed the assignment. I 1iked the possibilities of working in Team Ministry. We would be a base community of men and women, married and celibate, serving the ministry needs of the County. As models go, it is one of the best I’ve seen given the flaws of our Church’s ordained ministry. The Team was very supportive. They knew my background and history. They helped me to soften some of my rough edges and gave me needed guidance. There is no better place to start ones priestly life than in a rural setting. The parishes are small. I was the assigned administrator of the two smallest parishes, St. Anne’s in Logan, with one hundred families and Holy Family Parish in Mondamin with sixty families. My home was in Logan. I spent a lot of time just being with the folks. The smallness of the parishes allowed for a relaxed presence. I quickly got to know and be known by these two small communities. Some of the folks knew me by reputation. Most were wi1ling to give me a chance. The farm crisis had hit them hard. Many hoped this strange new bearded priest might have something to offer. I started having a home Mass once a week. This was a great way to meet the families, get a good home cooked meal and bring the Eucharist into their family lives.

The thing that surprised me most was how little it mattered whether I was conservative or a liberal, a traditionalist or a progressive. What mattered most to the people I served was whether I cared about them. Could I share in their everyday lives? They wanted a priest who had a deep faith, who was prayerful, sincere in his preaching and reverent in his liturgies, a man who could sympathize in their moments of grief and laugh in their times of joy, someone who revealed enough of himself to be called friend. They wanted their priest to bring to their lives a touch of the Lord. It surprised me how well I took to my pastoral duties. The parish structures were small; our Parish Councils met every other month. The folks knew better than I how to keep the parishes afloat financially. They had a better grasp of the maintenance and upkeep of buildings. The Liturgy committee had a good handle on the Church environment, the capabilities of the worshipping community and the needs of the liturgical life of the community. I tried to stay out of their way, lend a helping hand when I could and affirm what had already gone before me. That part was easy.

The first year I spent time listening. Visiting the sick and the homebound was very important. I also had a weekly mass at the nursing home in Logan. I tried not to show any favorites and to keep an eye out for the marginal and disenfranchised. I spent time with the elderly. A lot of what gets done in a parish is done by women – especially women over fifty who have raised their families. Listening to these good women’s stories, I got a true picture of the community. I made a point to affirm people as much as I could. The first year we had twelve funerals, a high number for the size of the parishes. I spent quality time with the bereaved families. This was clearly the heart of the ministry.

My basic sense of the job of a parish Priest is one who celebrates. He celebrates everything with his people, their joyful moments, their sorrowful moments and everything in between. It’s a job description well suited to my spirit. In short, I was having a good time and it showed. People appreciated a happy priest. Still it wasn’t long before the folks discovered that Fr. Frank had a different way of looking at the world. I put a lot of time and energy into my weekly homilies, making the connection between the scriptures and justice issues of our day. I wrote a weekly letter in our parish bulletin to keep them informed of my activities. I was always up front not doing anything they were not informed of before hand. I wanted them to hear from me what I was doing and why I was doing it before they saw me on TV or read about me in the newspaper.

Within a few weeks of my arrival I organized a line crossing at SAC in Omaha for August 6th. At my invitation five people crossed the line with a small pig to make the connection between the Arms Race and the Rural Crisis. The other two priests on the Team were among the line crossers. This set the whole county talking … something was up with their priest and they had better start listening.

I also spent time getting a handle on the rural crisis. I knew next to nothing about farming and I had to learn a lot quickly. Visiting with farmers and reading farm publications was very helpful to me. I went to conferences and strategy meetings throughout the state as well as farm rallies and protests. I pushed the idea of civil disobedience as an important tactic to be used in the effort. Most people were not open at first. Some began to understand slowly. I started planting white crosses and having a prayer vigi1 in front of our Court House every time there was a Sheriff’s sale.

As I got more involved in the rural struggle, I continued my resistance to the Arms Race and our Government’s policies in Central America. In my first two and a half years in Harrison County I received a couple of ‘ban and bar’ letters from SAC bases in Missouri and in North Dakota, was arrested in the Capitol Building in DC for protesting Contra Aid, and helped occupy the Iowa Governor’s offices in Des Moines over his sending the Iowa National Guard to Honduras. I was arrested in Nevada at the Nuclear Testing site. I spent a few days in jail, always during my vacation time.

Eventually some people got interested in doing civil disobedience on the rura1 issue. I was arrested with a man who was being evicted from his farmhouse in Adams County, Iowa. I organized a protest at a Sheriff’s sale in Harlan, Iowa where nineteen people were arrested while two hundred tried to yell down and stop the sale.

Not surprisingly, all my activism caused a great deal of concern within the parishes. Complaints were sent to the Chancery office. People were saying there was too much political rhetoric from the altar. They wanted to know how they were to teach their children to obey the laws when Father was breaking them. People started asking how I could be doing my job when I was always off protesting. Their priest was the talk of the wider community and an embarrassment to some. I had lots of one-on-one discussions. There were a couple of Parish community meetings. These were some difficult times for the parishes. My activism got mixed reviews. I had my detractors and supporters. A few left the parish and attended Church elsewhere.

Through it all I kept trying to make the distinction between following my conscience and being their Pastor. I made every effort to be a pastor to al1 regardless of their feelings about me. I made it clear that though there were two distinct aspects of who I was. I would continue to struggle with them both.

At first few understood what I was ta1king about. It took a while to develop a common language. Understanding came slowly as we began to share common experiences. Seeing me interact with them in important pastoral moments did a lot to break down the barriers. As our trust levels grew so did our mutual respect. I had to make some adjustments. Some people had to rethink their positions. Even today I cannot say many of my parishioners agree with the things I have done. Yet I feel I can safely say most respect me for following my conscience.

One thing I discovered in the past three years in this crazy country of ours is that people of good faith can come to opposite points of view on the most vital social and mora1 issues of our day. If we can’t agree, we can at least learn to respect and appreciate each other’s Faith journeys. Because all Faith is a gift, it is never earned. If the faith we have was freely given to us by God, who are we to question the Faith of others. Church communities also need to learn how to fight fairly and to disagree strongly without putting down the people they disagree with. These things were not covered in the Seminary. It is clear that those who embrace a Faith based resistance way of life will be a minority within the larger church. They both need each other. The resisters need the Church to give them a solid tradition to follow. The Church needs the resister to enflesh the prophetic Spirit of our time. The larger Church needs to find ways to affirm and to support this vital minority to foster a greater tolerance for conflict within the ranks and to develop the tools to deal with the tensions.

Last December 28th, 1987 on the Feast of the Holy Innocents, I crossed the line at SAC Headquarters again. I collected my 5th ban and bar letters from the base. There was a good chance I would probably end up going to jail. I spent the next couple of months preparing my parishes for this possibility. I made it clear in my weekly bulletin letters how I was going to deal with the indictment. I gave my reasoning for not seeking leniency before the court and how I fully expected to be sentenced to prison. I let it be known I was willing to talk to people about the matter. I spoke to many individually and held a couple of small group discussions. When the indictments were made, the trial date set and the sentence received, it was no surprise to my parishioners.

The success or failure of the last three years have a lot to do with how the parishes do in my absence. A part of any resistance life is doing jail time. How does one be a Pastor and in jail at the same time? Coverage for the weekends has been scheduled and a temporary administrator has been assigned. I do the best I can to keep in touch. I call Kathryn Epperson, my main contact and support person in the parishes twice a week to check in, find out who has been sick and what has been happening. When people are in the hospital or laid up I write or call. I continue to write my weekly letters for the bulletins. In them I share my experiences here in Prison Camp. I try to relate my message to the Scripture readings for the week. I also write about the events I have missed: Confirmation, First Communion, Graduations and the holidays. The parishioners have been most supportive. I answer over thirty letters a week, most of them from Harrison County. Folks keep me informed about what is happening in their lives and the life of the parishes. I’ve gotten photographs of the big events I have missed. The children’s religion classes have sent me letters and drawings.

There have been two deaths in the parish since I’ve been gone, one expected and the other not. I’ve called and talked to the family members. For one, a letter I wrote after her death served as the homily for the funeral mass. These have been the most difficult times of the separation.

Perhaps the most significant way I continue to be pastor is in prayer. I faithfully pray my “Office” plus I have been able to celebrate a private Eucharist daily. People have asked me to offer some of these masses for their loved ones. During my “Office” prayer and the Eucharist I lift up my parishioners in prayer, and mention those in particular need by name. Despite my physical absence, there has been a real connection between me and my congregations through prayer. When I am released I will return to Harrison County and resume my duties on the Team.

The dual tension between the pastoral ministry and resistance life has been a part of me from the very beginning of my priestly journey. Sometimes I have felt it pull me apart. It has not been easy to keep my balance. In a very real sense this parish priest – resister I have been writing about is a reflection of myself, a composite of my unique history, background and gifts. Yet not so unique others cannot see parts of themselves in my story.

A couple of years ago Bishop Dingman suffered a serious stroke that left him bedridden. He was forced to resign. It has been a very sad and painful time for him and the Diocese. Our new Bishop, William Bullock, inherited me. He has been fair and generous, willing to trust the process Bishop Dingman started with me. When I spoke to Bishop Bullock of the tensions I feel with these two pulls in my life, he suggested I visit Bishop Dingman and ask his advice.

I made the pilgrimage to St. Paul, Iowa, where Bishop Dingman lives with his sister who cares for him. The Bishop was in his bed, still paralyzed on the left side and in great pain. He was very tired and I could only visit for a short time. I told Bishop Dingman that Bishop Bullock had asked me to ask him for his advice on this matter. Bishop Dingman looked up at me and stared. Then he said, “Compromise!” He lowered his eyes. We sat in silence for a minute or two and then he looked up at me again and said, ”Do both!”

As I do my time here at Marion Prison Camp I think often of his advice and how I hope to continue following it in the future. As I stated in the beginning my time here at Marion Prison Camp has been one of review and renewal. What we have been doing in Harrison County these last three years is developing a model of priestly ministry that incorporates both resistance and pastoral ministry. Until the Church brings to life the concerns of peace and social justice on the Parish level, all the good words our Popes and Bishops write on the subject will come to naught. Justice and peace will continue to look like extraordinary and non-essential matters. A parish priest doing resistance is one way to bridge the gap between parish life and prophetic witness. Not every priest, or every parish, need embrace this kind of witness but some should and room must be made for their development.